About

Where the past intersects with the future.

Focusing on the physician patient relationship.

Plastic & Hand Surgeon

About Dr. James Clarkson

Born in Canada, I spent my early years in Toronto until age five, when my British parents returned our family to England. There, I was raised and later worked in the British National Health Service, training in plastic surgery until I was 38. In 2008, I moved to the United States with my American wife, eventually becoming a U.S. citizen. I completed a two-year Hand and Microvascular Surgery Fellowship at the Christine Kleinert Institute in Louisville and earned board certifications in plastic surgery from both Britain and Canada. My international journey has taught me that diverse experience fosters wisdom and that medicine thrives as a meritocracy.

From 2010 to 2025, I served as an Attending Plastic and Hand Surgeon at the College of Human Medicine at Michigan State University. During this period, my research drove me to simplify patient care, reducing risks and redefining the physician-patient dynamic. In 2016, I began performing hand surgery in an office setting using the WALANT technique—Wide Awake Local Anesthesia No Tourniquet—originally pioneered by Dr. Lalonde in New Brunswick, Canada. Noticing Michigan patients were used to sedation, I developed Virtual Reality immersive experiences to improve their comfort, leading to the creation of Wide Awake VR. This innovation has since equipped numerous surgeons with VR tools to enhance patient care.

Through years of VR application, I realized that beyond risk reduction, the patient experience during awake surgery was paramount. This insight shifted my focus. In 2025, my company evolved into WALANT Surgical Solutions (WSS), a medical services organization dedicated to connecting patients with surgeons offering awake hand surgery. WSS supports physicians in delivering exceptional office-based surgical experiences.

The industrialization of medicine thrives on complexity: intricate care enables remarkable surgeries when necessary—and higher profits. Yet, it also heightens patient risk, particularly from unnecessary anesthesia for minor procedures. You don’t need to be asleep for everything. Anesthesia, revolutionary in 1900, is overused in the aging 21st century, especially as more elderly patients undergo surgery. My practice bridges past and future, prioritizing a simplified physician-patient relationship while leveraging digital alternatives like VR instead of sedation.

By founding companies, I extend my role as a physician to tackle the “disease” of complexity at its roots. This includes building a network of surgeons committed to awake surgery in offices and operating rooms. WALANT Surgical Solutions is the first U.S. company to champion office-based surgery, with Heritage Hand and Plastic Surgery as its inaugural member.

Understanding Patients in their full context

I believe in the power of stories to transcend time. It is through stories that history can be alive, it makes us who and why we are. I listen to my patients’ stories to understand who they were, who they are now are and what drives them towards their dreams.

My Heritage

In 1989, during my interview for admission to medical school at the Royal London Hospital in Whitechapel, London, I was inevitably asked, “Why medicine?” My response was, “Because I want to be part of that story.” My childhood was steeped in tales of my family’s medical history, narrated by my father, a journalist who wrote stories for a living, and my mother, an operating room nurse who worked for a plastic surgeon. Growing up, I was surrounded by the artifacts and portraits that adorned the homes of both my grandparents. Many of these items are now displayed in my waiting room for you to see.

Medicine, like so much of our way of life, has been developing fast since my forebears first went into medical school in the mid-1800s. My family were British and New Zealanders. In those early days, much of the cutting edge of medicine was found to be in London, where they moved to follow their dreams. What I observe in their world isn’t markedly different from today’s. Medicine has advanced significantly, yet there remains much we are yet to understand. They treated real people with genuine ailments, strongly valuing the doctor-patient relationship, while also acknowledging the need to engage with technology and the broader systems within which they operated. Where they identified systemic shortcomings, they worked to rectify them; where technology could enhance medical practice, they were pioneers. They looked beyond the confines of their profession, engaging with the wider world, maintaining an international, open-minded perspective.

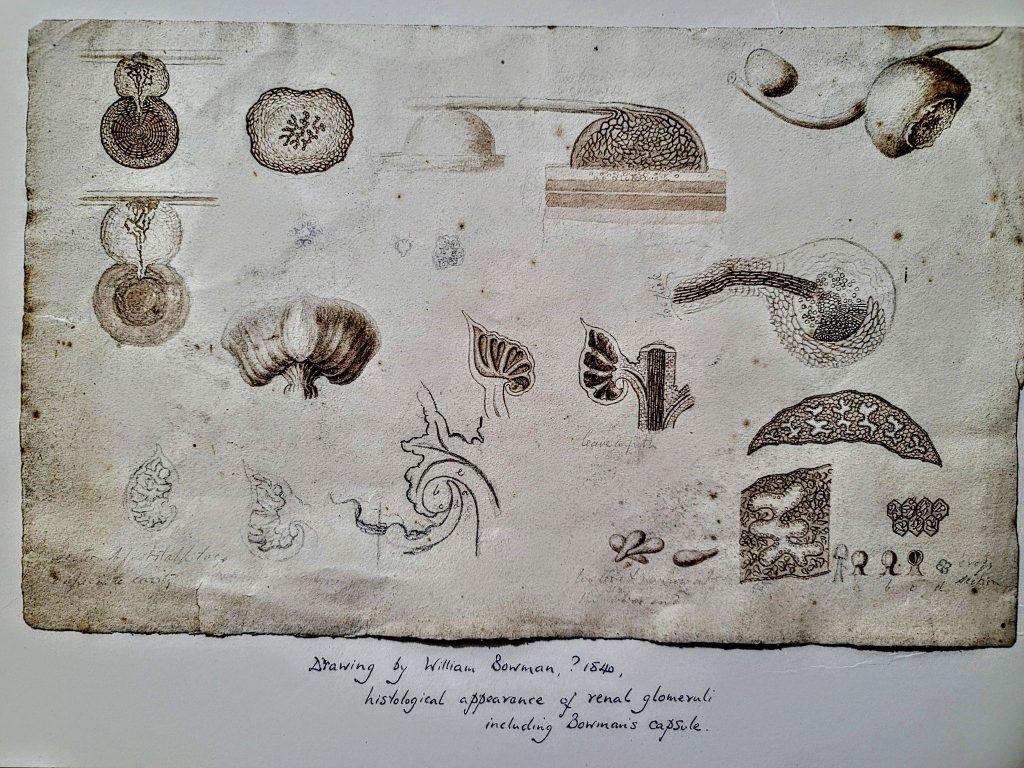

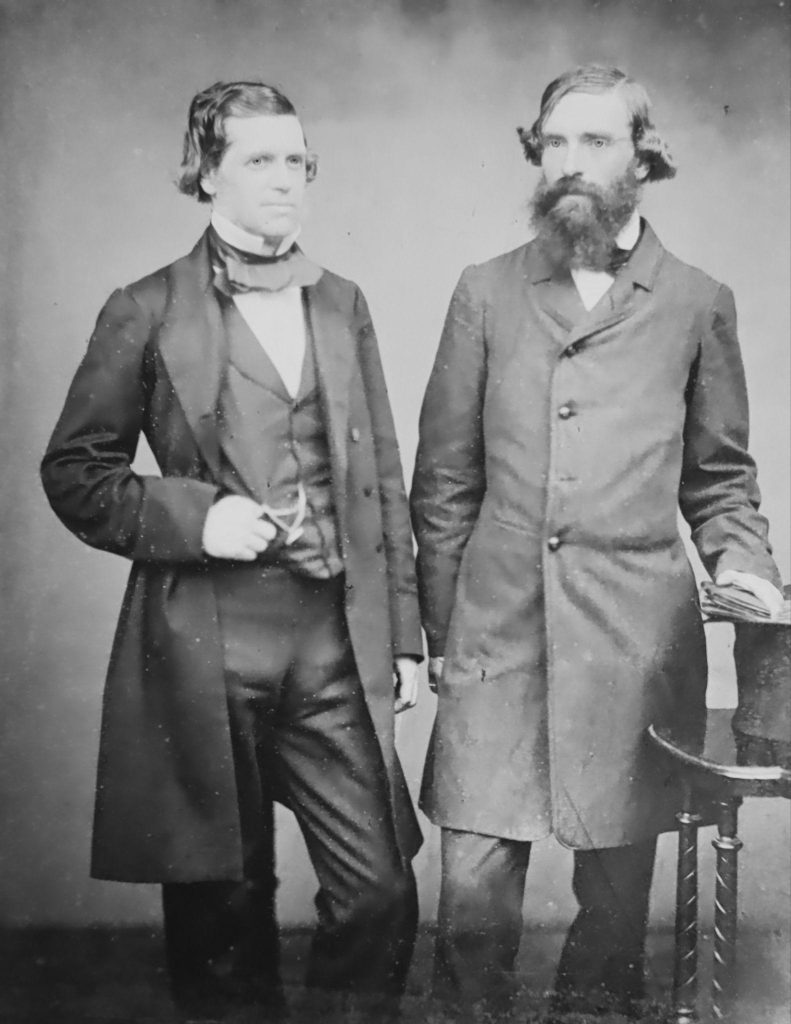

My mother, an operating theatre nurse, is descended from Sir William Bowman (1816-1892), who was an early ophthalmologist at Moorfields Eye Hospital, having been already highly familiar with optics from his undergraduate microscopic research. He spent those early years relating the structure to the function of smooth muscle, the eye, and the kidney. Typical for the era in which he worked, his name is now eponymous for many structures, such as the Bowman’s capsule in the kidney and Bowman’s layer in the eye.

As an ophthalmologist he worked closely with Albrecht von Gräfe, from Berlin, as they developed the new field of ophthalmology making early use of technology such as the Helmholtz Ophthalmoscope.

Together they pioneered early cataract and glaucoma surgery.

Bowman worked with Florence Nightingale to help set up the first British nursing college, the Nightingale Nursing School in 1860; we have many of the letters they wrote to each other when she was in Scutari, treating soldiers from the Crimean war of the 1850’s. She sent him many patients to treat back in London during this war.

Bowman writes that he went into medicine because of the relationship he developed with his own surgeon after burning his hand, when he was treated by Robert Bently Todd at the Birmingham General Hospital, England. I was fortunate enough to work in that old place as a plastic surgical trainee, long after it was repurposed as the Birmingham Children’s hospital.

Birmingham Children’s Hospital 21st century

Birmingham General Hospital 19th century

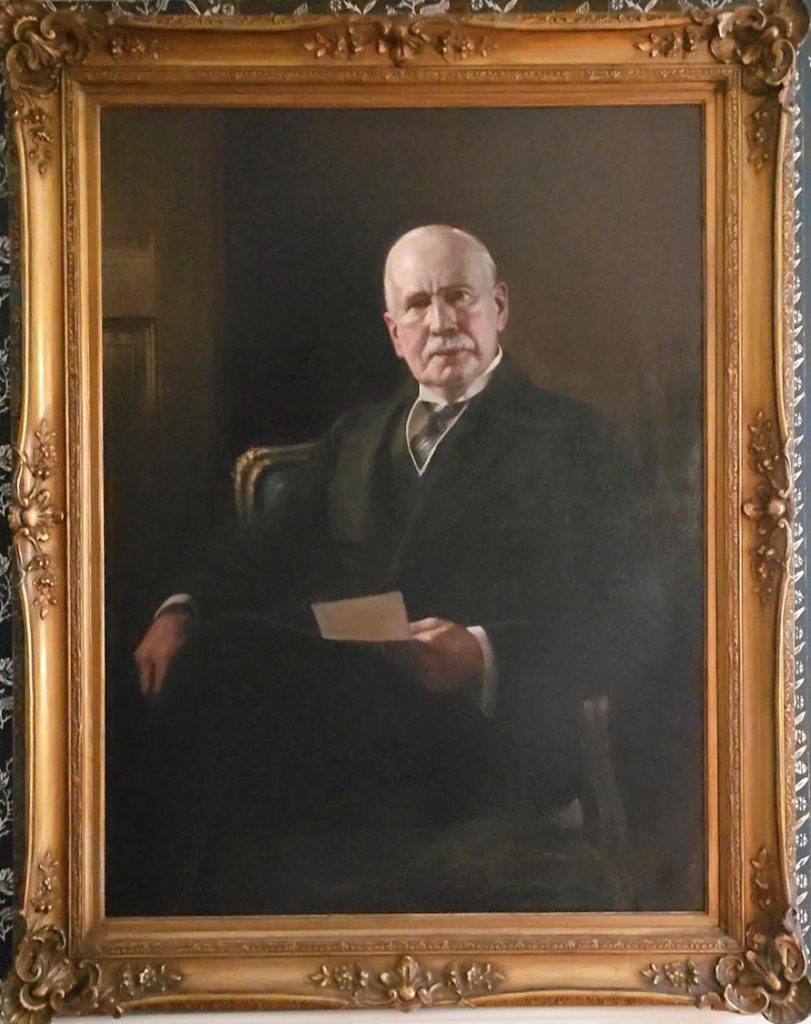

My father’s great grandfather Sir William Arbuthnot Lane (1856-1943) was a senior surgeon in the British Army during the First World War. He was horrified by the mutilating facial injuries he saw in returning servicemen from the Front. Recognising that medicine lacked any means to treat them, and that society rejected them, his empathy for these disfigured patients prompted him to lobby for resources to establish the first Plastic Surgical Specialty service in the Cambridge Military Hospital in Aldershot under the leadership of a New Zealander, Harold Gillies.

Because Lane recognized that Gillies’ unique pioneering facial plastic surgery needed support, Gillies is now recognised as the father of modern Plastic Surgery.

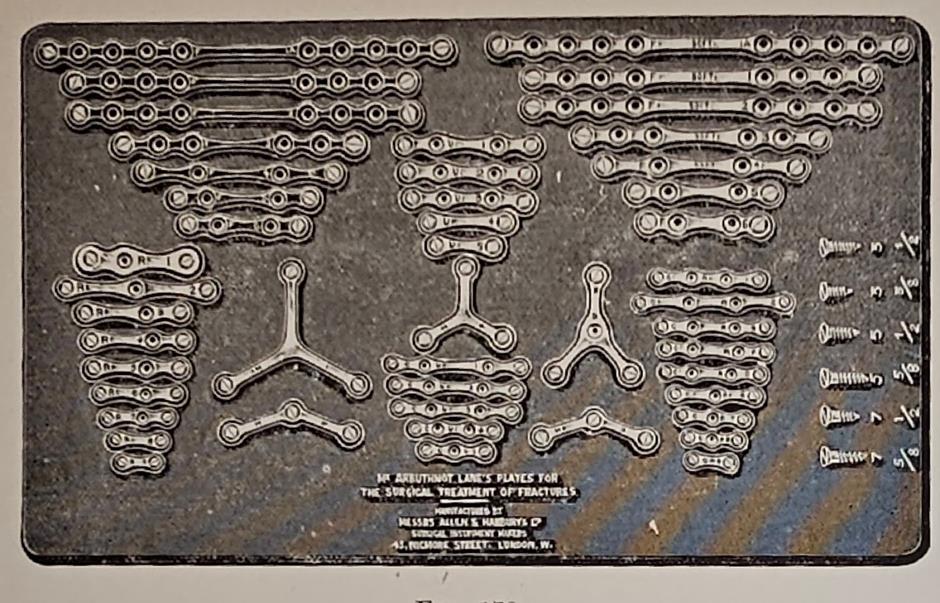

In his younger years Lane has been a surgical polymath, pioneering surgery for cleft palate, large bowel resection and the first surgical management of fractures. He was responsible for introducing new technology to enable surgery to become safe. In 1900, unsatisfied with the current treatment of fractures seen in orthopedic surgery he introduced the autoclave to London from Germany, and then was the first surgeon to use orthopedic plates on fractures using this technology to prevent infection, before the invention of antibiotics.

He is well known for his phrase “If everyone believes a thing, it is probably untrue!”, this serves me as well in the 21st century as it did him in the 19th and 20th.

My Grandfather, Patrick Clarkson (1911-1969) was a World War II era Plastic and Hand surgeon in London, and married Lane’s granddaughter. Son of a New Zealand sheep exporter, Patrick wrote his own story by leaving for London as a young man. He became a second generation Plastic Surgeon, directly trained by Harold Gillies during WWII and the New Zealanders went on to share their practice after the war. He was appalled by the extended delays wounded soldiers faced before receiving treatment for their facial injuries, burns, and hand injuries. Consequently, he organized much faster treatment plans, discovering that early excision of burns followed by skin grafting saved more lives. He also found that by closing facial missile wounds promptly, there were fewer bone infections and quicker reconstructions. He achieved this by sending a forward unit near the front line to get to the soldiers before they were evacuated. Much of this history was related to me by his trainee during the war, Rex Laurie who was sent in a forward unit to the battle of Casino, whose stories from those times run deep. Clarkson’s WWII work reflects his rejection of the way the “system” would treat his patients, he was not confined in his thinking, he looked outside of the operating room to find his solutions. Later he went on to describe Poland’s Syndrome, which is a congenital deformity of both the hand and the breast, as well as early work on gender reassignment for patients with intersex in the 1950s.